Harry Moroz

Financial Reform or New York Deform?

On Wednesday morning Politico picked up the dustup between New York Senator Chuck Schumer and Mayor Michael Bloomberg, describing a perturbed Bloomberg lashing out at Schumer for "turning against" Wall Street. Schumer has offered support for the financial reform bill now moving through Congress, while limiting his day-to-day involvement with the bill to avoid the appearance of actively attacking his "hometown industry." Bloomberg, on the other hand, feels that his congressional delegation is biting the hand that feeds it, and biting down hard.

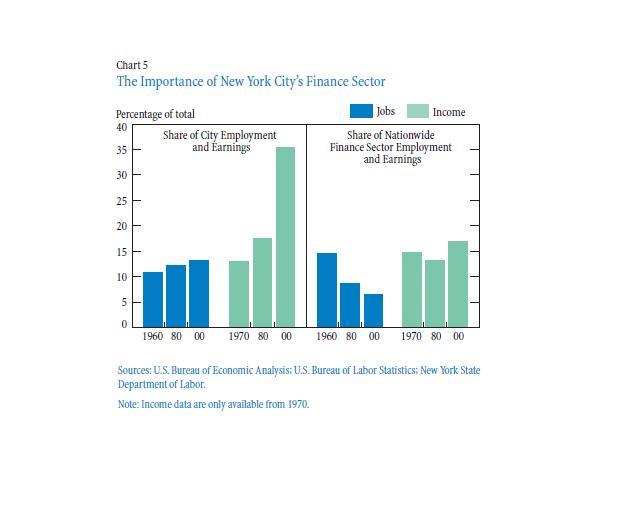

Bloomberg's concerns are understandable. The financial services industry and the securities industry, in particular, are important to New York City's economy. Financial services accounts for 12 percent of the City's employment and around 30 percent of its wages (the securities industry accounts for 5 percent of jobs and 24 percent of wages). Financial services is also an important source of city revenue with the securities industry contributing 12 percent of City tax revenues prior to the crisis. The New York State Comptroller estimates that each new job in the securities industry creates two additional jobs in other industries in New York City. It would seem, then, that any effort to crack down on the financial services industry and on the securities industry in particular would return the city to the poverty and crime of the less glamorous 1970s by undermining job creation and the fiscal health of the city, right?

Certainly, there is an argument to be made that the financial reform bill would actually help New York by protecting it from an industry that has shown itself capable of unleashing financial crisis upon its host city and the entire country. But will the financial reform bill truly have the devastating impact on financial sector employment and earnings that Bloomberg expects?

The chart below (source) demonstrates that even as the share of city employment accounted for by the financial sector has inched up, the share of nationwide employment accounted for by the City's financial sector has decreased markedly. Still, the citywide and nationwide shares of earnings have both increased quite dramatically since 1980. From this, the New York Fed concludes that "the city has retained and expanded the higher-paying, relatively sophisticated activities in the sector even as it has shed relatively lower-paying jobs."

This means that Mayor Bloomberg is almost certainly right that the financial reform bill will negatively impact financial sector employment and earnings. If nothing else - and even if the legislation completely omits executive compensation reform - the bill will regulate some of the riskiest (and so most profitable) practices of Wall Street firms and impose leveraging and other requirements, in turn limiting revenue and the need for and compensation of the highest-paid traders (the ratio of compensation to revenue at Goldman Sachs since 1999, for example, has been relatively constant).

The important question, however, is whether this is a bad thing for New York. Certainly, in the short term, as Michael Sherer points out, there will be fewer bottle-service clubs and more empty tables at restaurants. And the city's fiscal condition will suffer somewhat, as it would have this year if the federal government's financial bailout had not made money so cheap.

But in the longer run these graphs demonstrate the City's dangerous overreliance on a tiny, wealthy group. In fact, financial sector employment in New York has been shrinking: the City has lost 100,000 financial sector jobs over the past 20 years. New York is losing out on broad-based financial services employment, while holding onto a relatively small number of very high-paying jobs (the average New York City salary in the securities industry grew 73 percent since 2003). The two additional jobs the State Comptroller says are created by each new job in the securities industry are mostly in retail and restaurants, the result of "increases in household consumption." These jobs are low-pay and low-benefits employment and it is unlikely that they can continue to be created, especially in an economic downturn: as individuals grow wealthier, their consumption decreases and they save more (lower-income households, in contrast, spend most of the money they make). Fewer, wealthier financial services professionals cannot continue to support a robust New York City economy.

Even if Mayor Bloomberg is right and the financial reform bill reduces financial sector profits (which could be a great thing for the economy as a whole), New York City's economy will benefit. The reform bill will increase stability and prevent future shocks to the financial system. But those are once-in-a-lifetime events. Reducing New York's reliance on wealthy securities workers could refocus the City's financial services industry on less profitable, less risky activities and realign its economy to foster more good jobs that permit a middle-class standard of living.

Harry Moroz: Author Bio | Other Posts

Posted at 5:13 PM, Apr 21, 2010 in

Permalink | Email to Friend